Leadership’s charge can be referred to as “change for better results.” Leaders identify an aspect of their organization or business and understand that change must occur. Whether it is a process that isn’t working or a market that isn’t yielding results, something has to give. One of the most dangerous things a leader can do is nothing at all.

It appears logical to decide to make monumental changes when things aren’t working, but what if everything appears to be normal? Sure, conditions are favorable now and the organization is making money, but it is incumbent upon leaders to anticipate the future hurdles. How does leadership instill a sense of urgency while avoiding feelings of changing for change’s sake, or simply sounding like Chicken Little? There are plenty of leaders who appear more like a Baskin-Robbins, engaging in the “Flavor of the Month” club. They read the latest business bestseller and quickly make it the firm’s dogma. However, a new book becomes gospel the next month, leading to confusion and frustration. So how does a leader make real, sustainable change when doing it the old way feels so good?

Selling the Upside

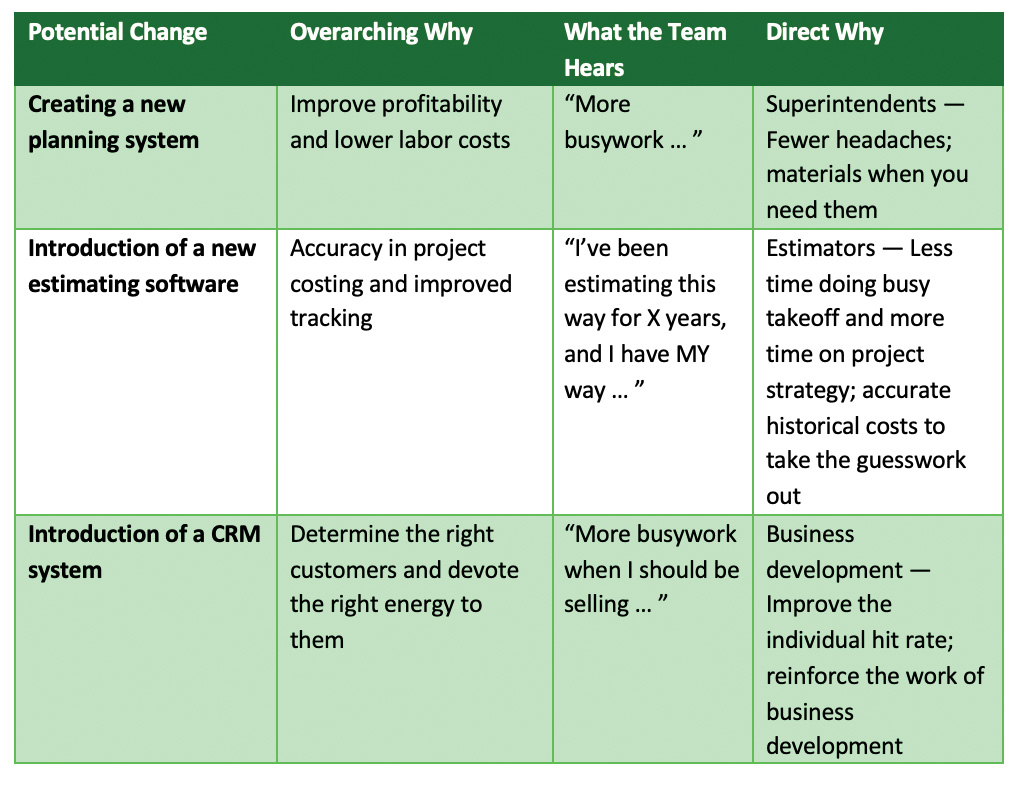

Whether the reason for the change is immediate or long-term, leadership needs to address the “why.” Interestingly enough, the “why” may be different for different team members. For instance, it is easy to discuss a change being made to generate higher profitability. That sounds like a compelling enough reason for any audience. However, if the leader is creating wholesale change to a rank of superintendents who will see a drastic change in the way they need to perform there may be blowback: “Great, I have to change the way I’ve been doing it so the firm can make more money.” Consider the examples and the potential variations in messaging in Figure 1.

There is no shortage of reasons why success or failure can be rooted in the messaging. Many people despise change. Humans adapt and develop behaviors that allow them to maximize performance. Ultimately, there is a comfort that comes from that mastery, and when someone then tells them to “stop and do it differently,” it creates frustration. The right message is: “Continue, but tweak and refine.”

Selling Collaboration

Once the “why” has been sufficiently answered, there needs to be a game plan and follow-through. Another area that is often overlooked is the need to involve the people who will be impacted by the change to be strongly involved in the implementation of the change. For instance, one of the gravest mistakes in software selection is to not involve the right teams in the process. Far too often, a system is selected in a vacuum by an information technology team that will not use the system. A team of project managers, field leaders and administrators should have a voice in the selection process and customization of that solution. This does not mean that every project manager should be on that committee, but rather a fair representation of the practitioners who will objectively evaluate and contribute to rollout.

One of the greatest reasons to involve practitioners in any change initiative is the creation of evangelists. Sure, leadership and IT want to see a new software be a success. It cost a fortune and the salespeople promised the world. When they talk about it being the “right choice,” it is easy to scoff at their remarks. However, when a fellow project manager talks about how they used the new tool, software, process, etc., and how it provided value, it seems to have a different feel or sentiment. Creating buy-in with fellow members of the team helps drive long-term success.

Selling the Overhaul

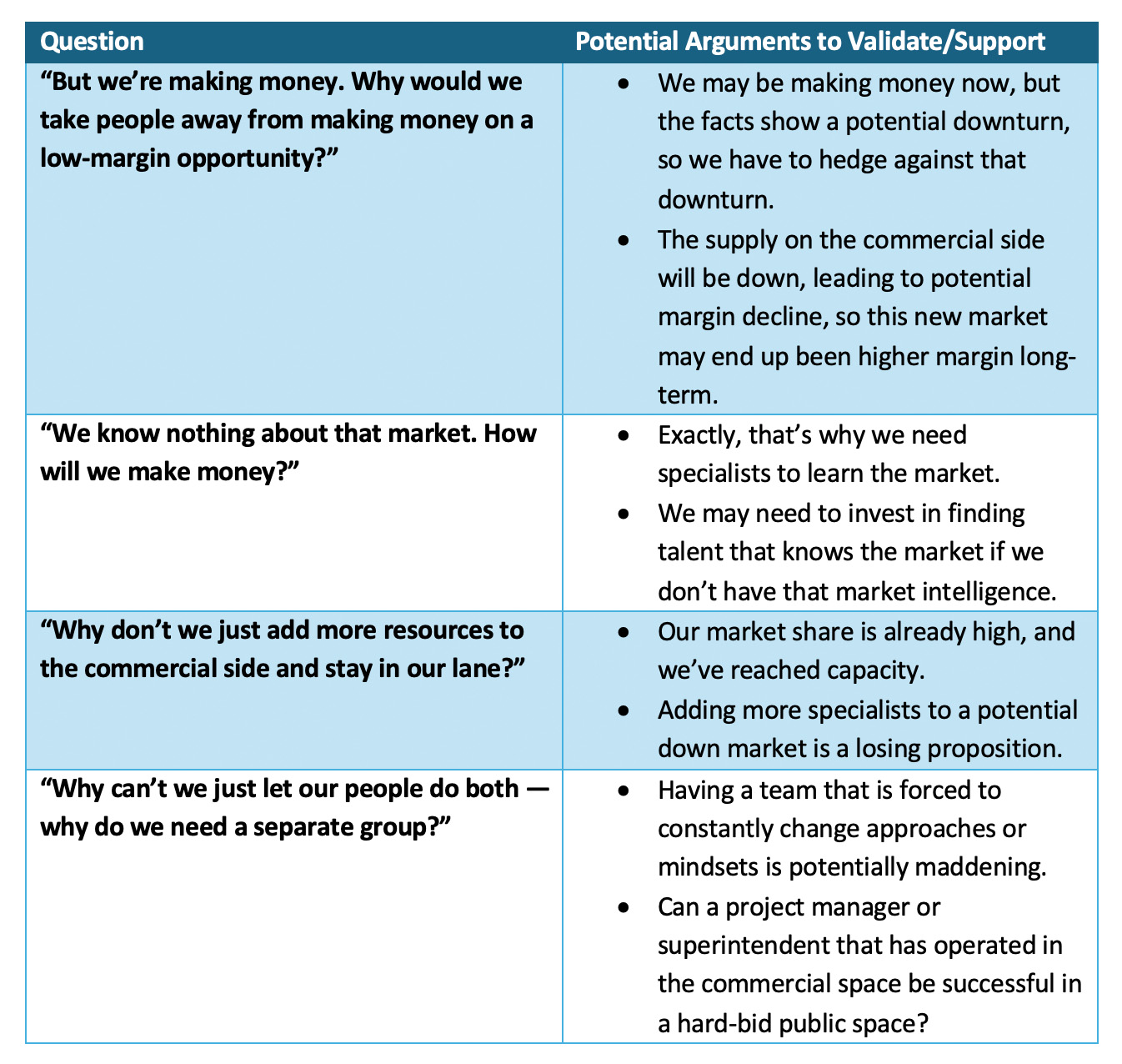

Some changes seem hygienic in nature. Rolling out a new software platform, while never easy, is somewhat expected. Upgrading the toolkit is part of the job. However, what if the change is much more dramatic, like opening a new office, adding a new service or even discontinuing an offering? More importantly, how does one drive this change when the current market conditions are favorable and it means potentially shorting a group that is riding those favorable conditions? Consider this case:

An organization has operated in the commercial space for its entire existence. It is current market, it has decent market share currently in its operating geography, but it also sees a decline in commercial offerings in the next three to five years. It is considering opening up a division or group that will operate in the public or municipal space. However, this will potentially require several managers, estimators and superintendents to shift away from the commercial space.

Leaders have to immediately recognize the litany of questions that they will be peppered with a formulate a response that is both realistic and forward thinking (Figure 2).

Presenting effective counterarguments is never an easy proposition. There is also a fine line to maintaining a strong argument and also being an effective listener. For instance, there may be contrary themes that are not only factually correct but also serve as a suitable rebuttal. Leaders avoid idea fixation at the right times but allow enough conversation to allow people to get comfortable with the change in the right time.