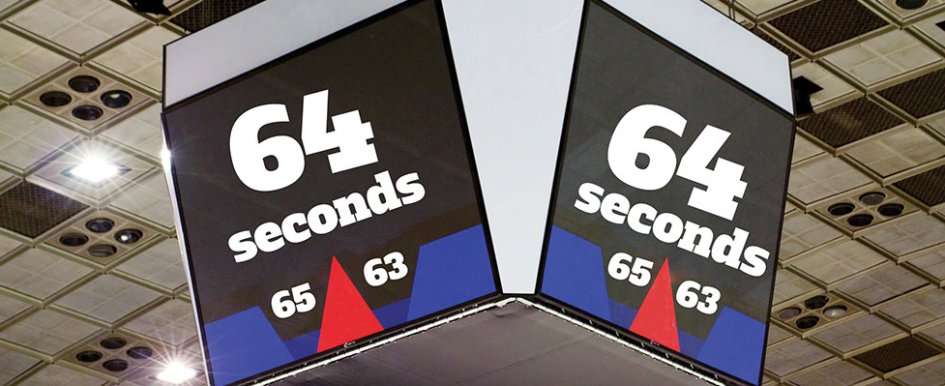

64 seconds.

No, this isn’t me breaking my diet so soon after declaring a “new me” after stepping on the scale again. And yes, this may look like a complete fanboy moment, seeing as how I do bleed orange and blue. 64 seconds is the amount of time that the University of Florida’s men’s basketball team were leading in the 2025 national championship game. The readers from Texas might also be popping an antacid tablet as they see this, and for that I apologize. In truly one of the best championship runs, Florida ended up winning 65-63 against the University of Houston.

Those who watched the game know that Houston was winning for 99.94% of that game (maybe no antacids, but blood pressure meds were on tap). There was a 12-point run where momentum shifted, and Florida ultimately secured its third basketball national title. As I sat in my recliner with the biggest smile on my face — purchasing my national championship “drip,” as the kids would say — I immediately started thinking about how the Gators might be memorialized in sports history, but also how they might be the best-in-class mark as a construction closer. Let me explain.

Leading Isn’t Winning — Finishing Is

So many of the organizations that I see discuss their ability to begin a project well, only to see their lead dwindle as it enters the home stretch. The punch list looks more like a novel than a quick summary, collecting closeout documents looks more like guessing the numbers in the Powerball and as-built drawings are reminiscent of a 4-year-old’s coloring book. The final stage of the project probably should’ve been 64 seconds, but the entire project team is chugging Gatorade and sucking oxygen in the trailer, barely capable of mustering any energy. That is also under the grand assumption that the project team assigned with the completion is even the same team that started the project, since a preponderance of contractors have a tendency to pull their starting team. Imagine if my team had decided with 64 second remaining to put in that true, walk-on freshman who has only touched the ball when it rolled near him while on the bench.

There may be something in the “start” that requires more depth of understanding. None of the readers have ever muttered the following:

- “We will do whatever the client wants at the start: We get awarded a job on a Friday, and we’ll start that Friday if

need be.” - “Getting started is simple: We throw together a job book, do a handoff/dump and throw bodies at it. We’ll throw A LOT of bodies if we need to. ”

- “We start like a thoroughbred, coming out of the gates strong.”

Interestingly enough, I have heard that last quote amended to include “but they sure do finish like a mule.” It is almost as if the construction community either fails to plan for a full game, losing steam in that last moment, or they think those small, tedious details at the end will finish themselves — only to create a death by a thousand paper cuts.

Why Closeout Consistently Breaks Down

It is a mind-boggling phenomenon when you consider how many organizations truly struggle with this phase of work. Consider the reasons that could be root causes of closeout failure:

- Unknown expectations of what “done” looks like from the customer’s perspective

- Unknown expectations about what the city, municipality or agency will require at the conclusion

- Supervision shuffling toward the end because of new project demands

- Distracted project leadership and an inability to finish the paperwork, possibly rooted in euphoria also created by new project demands

- Clients that are not motivated to get done when you want to get done

- Clients that have a never-ending “shopping list” of extras that complicate getting the base contract completed

- Clients that see the contractor as a “free maintenance staff”

Not all of these reasons specifically mean that the contractor exhibits a lack of control or weak operational execution. For instance, there are plenty of contractors deeply invested in fanatical customer service, and something like the last bulleted item may be a customer that is abusing a relationship. However, there is also a difference between a one-off client situation and a systemic breakdown within a business that consistently erodes margins and burns extra general conditions well past the final game buzzer.

Designing a Repeatable Exit Strategy

Closeout, or a firm’s “exit strategy,” should be as well defined as a firm’s kickoff strategy. Some of the closeout best practices should include the following:

- Preconstruction strategy — If you call your project start a “handoff” or “turnover,” please stop. This evokes a baton toss rather than a collaborative and structured strategy. More importantly, does a weak startup lead to an even weaker finish?

- The end at the beginning — “Begin with the end in mind” was a famous phrase, hardly invented by me. However, Stephen Covey clearly understood that closeout needs to be an integral part of preconstruction

- Determination of the start of closeout — Every firm has that moment where either closeout begins or when personnel transitions to a new project. Identify when the exit strategy process should begin in either case.

- The closeout meeting — Whether it is assigning punch list ownership or determining a timeline for document collections, each project should have a firmwide consistency closeout meeting

- Client management — Sure, the specifications say one thing, but how intimately does your client understand what done looks like? Better yet, do you know what they expect at the conclusion? How are you managing or exceeding those expectations?

- Measurement of closeout — How long is the process taking? What metrics are you using to measure the efficiency of your closeout process?

Consider the last item. Imagine your marketing or preconstruction team being able to use a metric like the following: “Our construction team has a closeout process, and our firm typically finishes a job 10% ahead of schedule compared to our competition,” or “Over the last five years, we have a year-over-year improvement on our projects of 4.3%.”

It is also important to ask your team about the “final date” they invest all of their energy in. It is possible that your team has made it a practice to focus on the two of worst words in the industry — substantial completion — rather than the ones that have the real power: final acceptance. Too often, there is a sense of urgency tied to substantial completion, only to see an organization take its foot off the gas in that final push.

Maybe that is where Houston failed to convert … they certainly had the first 99% down, but history will remember how Florida finished the game.