Why won’t my employees just do what I tell them? Why am I struggling to motivate my team? Why aren’t they giving me the performance I need? If any of these questions sound familiar to you, you’re not alone.

You were probably promoted because you’re a competent technical professional. You know how to build a bridge, negotiate a deal or justify a capital expenditure. But, whether you’re a middle manager or a CEO, your technical skills usually won’t help you be a better leader.

Effective leadership has an undeniable business value. One study examined the best and worst leaders at a large commercial bank and determined that, on average, the worst leaders’ departments experienced net losses of $1.2 million, while the best leaders boasted profits of $4.5 million.

Sink or Swim is Not a Plan

As any disgruntled employee will attest, exceptional leadership isn’t commonplace. One recent Center for Creative Leadership study reveals that up to 50 percent of managers are ineffective. Sadly, your company probably isn’t doing much to help. They might use the wrong criteria to select managers, focusing on technical ability rather than leadership skills. Most companies invest precious little in development and training is often an isolated, one-size-fits-all event. Without follow-up, 90 percent of information from training programs disappears after three months.

Without organizational support, leaders who want to improve are left to their own devices, but a simple search for leadership books on amazon.com results in more than 100,000 options. No wonder leadership feels so complex. Luckily, there’s good news. Though psychologists once believed leaders were born and not made, recent research tells a much different story—leadership is an acquirable skill. A recent study by Richard Arvey at Singapore’s NUS Business School revealed that 70 percent of leadership is learned. That means anyone can learn to become an effective leader.

Two Behaviors All Leaders Must Master

For decades, scientists have known everything we need to know about how successful leaders behave.

In 1945, a group of Ohio State University researchers set out to disprove the notion that leadership was an inborn personality trait. With 70 International Harvester Company foremen as subjects, the group discovered that leadership effectiveness was related to the presence of two independent behaviors.

First, effective leaders showed consideration—displaying support, compassion and friendliness to their team.

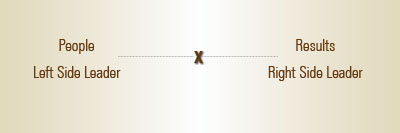

Second, they initiated structure. They clearly defined the role each employee played and drove performance. Let’s rename these behaviors “people” and “results,” respectively.

Indeed, you probably feel an inherent tension between people and results. On one hand, you must build relationships by connecting with your team, earning trust and motivating. On the other, you must drive top- and bottom-line results through performance and productivity. Leaders think, “I can drive them to perform,” or “I can be their friend.”

Depending on your upbringing, culture and role models, you’ll find a comfortable position between the two. For a select few, that position is directly in the middle, leveraging each outcome to support the other. The rest fall somewhere to the left or the right, and some to the extremes.

The best leaders move to the middle, focusing on people and results.

The best leaders move to the middle, focusing on people and results.Left-side leaders focus on the happiness of their team at all costs. They don’t set expectations, give honest feedback or make tough decisions. Working for a left-side leader might be pleasant at first, but as soon as you need tough—but true—feedback, he or she would freeze.

Right-side leaders drive results so aggressively that they leave a trail of abused employees in their wake. This leader requires grueling hours, is never satisfied and withholds recognition lest people become complacent. Though right-side leaders help you up your game initially, in the long-term, you suffer both physically and mentally.

The best leaders are able to move to the middle, focusing on people and results. These bankable leaders create prosperity in the form of achievement, health, happiness and wealth for themselves, their teams and their organizations. Think of the best manager you’ve ever had. He or she might have been a walking contradiction, achieving all of these things at once:

- Care for and understand team members AND set aggressive performance targets

- Help team members succeed AND expect responsibility for successes and failures

- Provide recognition AND push continuous improvement

- Help you enjoy your job AND ensure everyone maximally contributes

From music to science to athletics, people with average talent have achieved extraordinary things. Scientists used to think that superior athletes achieved greatness because of biological differences. But, we now know that the best marathon runners, for example, simply train more in the weeks leading up to the marathon.

The same is true for exceptional leaders. That’s why the “I just wasn’t born to be a leader” excuse doesn’t

hold water.

A person may not want to be a leader, which is entirely different, but with focus and commitment anyone can become a more effective leader. The daily commitment it requires isn’t always exciting—but will make you a more bankable leader.

Three Actions to Become More Bankable

1. Gather the facts

Begin your journey by truthfully evaluating your own behavior. You may have placed yourself in the middle of the continuum, believing you place an equal emphasis on people and results—but your team might completely disagree. Use your resources and gather the facts, whether it’s through an assessment or feedback in the form of conversations.

2. Be laser-focused

For executive teams, research shows that as the quantity of goals increases, revenue declines. Similarly, leaders often choose too many development goals. Give yourself the greatest chance for victory by developing one thing at a time. It is far better to make progress in one area than to make little or none in five.

3. Practice daily

It’s likely that you’ve once had a development plan that gathered dust in a drawer. You were probably engaging in delusional development—the futile hope that just by wanting to get better at something, and knowing enough to be dangerous, you’d improve. The amount of deliberate practice you choose will be proportionate to your improvement.