If you have ever called your preconstruction planning process a “dump” meeting, “handoff” or “turnover,” please stop. Most preconstruction planning looks like it is trying to set the world speed record for paper shuffling. “Here are the plans, specifications, submittals, contact list, map to the jobsite, emergency phone numbers and some aspirin. Any questions?” No one can argue that the preconstruction phase is not a frenetic time of preparation. For many, it is a fine balance of joyful exuberance and the anxiety of wondering if you’ve left something off the bid. Too many organizations look at preconstruction planning as an extremely transactional process. If your preconstruction process is more of a dictation than a collaboration, you might be doing something wrong.

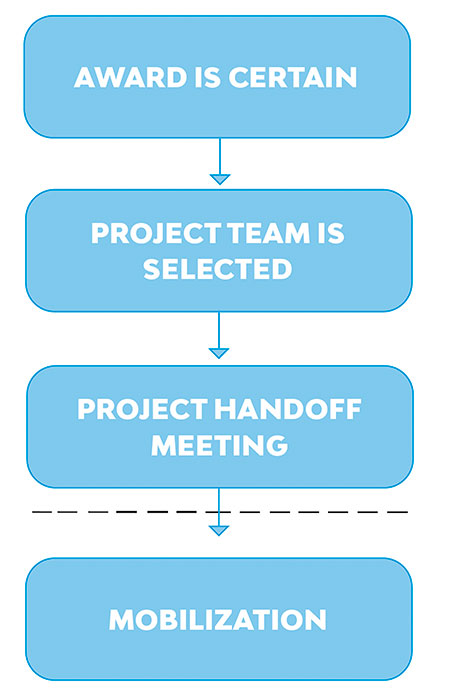

World class preconstruction planning is actually more about project strategy than simply checking things off a master list. Consider the illustration in Figure 1. Everything in Figure 1 above the dashed line appears to be business as usual. Assuming there is a level of consistency in the documents that are being shared from the office to the field, one might argue that nothing is amiss.

However, real preconstruction strategy is so much more in depth and should have a level of problem solving that only comes from collaboration between the estimator, manager and superintendent.

The Homework Phase

First and foremost, Figure 1 is accurate to a point, and there should be some sort of information transition. For many organizations, a physical or digital “superintendent job book” is created. However, the next step requires some homework.

After the handoff, the superintendent spends some alone time with the drawings and estimate to familiarize themselves with the project. Many organizations provide some sort of “cheat sheet” to focus the reader on specific attributes of a project to avoid it feeling like some sort of engineering Easter egg hunt. For instance, some of the questions in the homework phase might include:

Where would we stage the project? What is our history with this design team? Do we know their nuances in their design approach? What are some of the normal, often-missed details? How well overlaid are the various scopes (i.e., mechanical, electrical, structural)? Are they even using the same backgrounds as a basis for design?The whole intention of the homework phase is to create a common platform so when there is an actual meeting of the minds, everyone comes to the table aware.

Up to this point, the approach has assumed the estimator and the project manager are the same person. If the estimator and project manager are two different people, the same approach should be taken here.

Preconstruction Collaboration

Once everyone has a fundamental working knowledge of the project, the team can now engage in real problem solving. This is where discussions about project details gets productive. For instance, some of the exchanges that can now take place include the following:

Phasing — The estimator can explain their logic and then hear from the superintendent about their approach. If they don’t align, hopefully the team can leave with an effective and constructable plan where there is ultimately buy-in across the units. Trade partner involvement — One final review of the potential project team is healthy and also provides additional buy-in from all parties when there is candid discussion about a trade partners’ past performance. Crew sizing — Every project can be built an infinite number of ways. The same can be said for crew composition. Reviewing the productivity targets and crew blend in this setting is a healthy conversation to have, especially when it also relates to budget enhancing ideas. Equipment utilization — Similar to crew sizing, there should be a proactive dialogue about the right equipment and how it can be optimized.There are plenty of conversations that should be had prior to mobilization but in the spirit of getting the first shovel in the ground, those conversations are often ad hoc or even discarded. Real preconstruction planning should be conversational.

Final Game Plan

The last step of true preconstruction planning is about vetting those final assumptions among a group within the organization, most likely the leadership team. Reserved for larger projects, this final game plan stage ensures that there is a real winning strategy. For instance, the project team might present the following approaches to senior management:

Margin enhancers — What approach will the team take to drive margins higher? Customer satisfaction — What will the team do to drive superior customer satisfaction? Safety hazards — What will the team do to attack job-specific safety challenges? Trade partner concerns — Where does the team feel there are potential liabilities in the supply chain or trade partner team?Ultimately, this phase is not to discuss superficial items. For instance, when asked about the safety plan, an answer like, “We’ll ensure all of the team wears personal protective equipment,” should be met with dubious pessimism. Put another way, if this is the best you can come up with on a project with a 20-foot excavation, high-tension power lines, a school next door and roof that is 100 feet high, you might want to go back to the drawing board. The senior leadership team should play the role of the devil’s advocate, challenging those project assumptions about everything, leaving nothing to chance.

The irony of naming the preconstruction process a “turnover meeting” is not lost as a theme. When handing off the ball, if the transition from the quarterback to the running back is flawed, there is a high probability of a fumble. A capital sin in football is turning over the ball. When done incorrectly, preconstruction fumbles can lead to catastrophic losses that look really bad in the box score.