This article is the third of a four-part series in which Walker Lee Evey will share how he helped turn the Pentagon Renovation Program into one of the nation’s most successful design and construction projects.

The two previous articles in this series discussed challenges faced by the early Pentagon Renovation Program and our subsequent efforts to form and empower integrated teams. As a result of these program adaptations, we were better prepared to focus talented personnel on implementing new business models. But the question remained, upon what new business models would these talented people actually focus?

We were convinced that improving the execution of the inherently inefficient existing business model, known as design-bid-build, would not produce the performance breakthroughs we sought. We needed a new way of doing business, and a model that would increase our effectiveness across the board. Our first breakthrough came via a Washington Post weekend article about home remodeling. I clipped the article and brought it to work.

It made the point that design-bid-build, with separate contracts for architects and construction contractors, often resulted in disconnected planning and execution. In fact, it frequently caused the two parties to become adversaries, working at cross purposes. This produced aggravation for the owner as it drove unnecessary increases in cost and schedule—the very problems being experienced by the Pentagon Renovation Program. The article recommended the use of a single contract in order to hire the architect and the contractor as a combined, integrated team.

During a discussion of the article, a young manager informed us that it described a new delivery model called design-build. Some of the more senior personnel in attendance countered that design-build was “against the law and not used by the government.” Furthermore, they claimed, it didn’t work.

Although the model was seldom used in design and construction, I knew from experience that identical models were the standard of practice for modern programs in other fields. Furthermore, common sense dictated that designers and contractors should be as tightly integrated as possible in order to optimize talent and reduce uncertainty and waste.

Subsequently, a quick review of the Federal Acquisition Regulations (FAR) revealed that design-build was not only an acceptable model, but had also been incorporated into newly-written sections of the FAR. Recent far-sighted

legislation had promoted new language and policies in the design-build became our new business model.

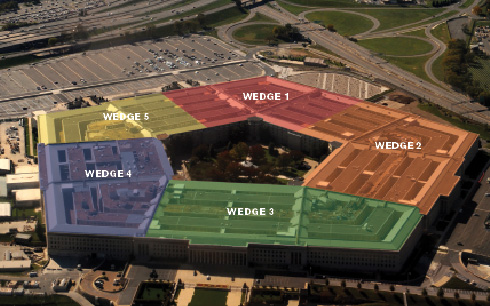

Meanwhile, we had to continue moving forward with projects already planned and structured as design-bid-build that were too far along to change direction. For example, Wedge One, the first of five chevron-shaped wedges that together make up the above ground Pentagon, had a completed statement of work and prescriptive spec package that totaled 3,500 pages. Much work had already been invested in developing a standard design-bid-build solicitation. To fundamentally change direction at this point would be impossible, so we implemented a few modest alterations (such as using best-value source selection in lieu of award to a low bidder) and pressed on.

In the interim, we worked to craft the form our future design-build contracts would take. If we were to move away from traditional prescriptive requirements composed of detailed designs, drawings, specifications and standards, what would replace them? What would these new contracts look like and how would we accomplish a meaningful competition?

After many hours of discussion we concluded that we would recast our contracts in a fundamental way. We chose the term “aspirational contract” to describe our new approach. In our aspirational contract, we would capture and communicate our goals, express our intent, describe our relationships and depict our vision for the future instead of just communicating detailed prescriptive requirements. It sounded touchy-feely, but it was firmly based, in part, on historical rules of contract interpretation I had learned in court during several hard-fought contract disputes earlier in my career.

We added a new section to our contracts, called a preamble, preceding the government’s standard uniform contract format. It succinctly, but explicitly, set forth our aspirational goals. This document, consisting of less than five pages, ultimately served as a touchstone over the life of each contract. It communicated a contract that operated in human terms rather than just through explicit technical detail. Listed below are some of the verbatim principles addressed in the preamble.

Next we took on the challenge of figuring out exactly what would replace prescriptive designs, drawings, specifications and standards. We devised an approach using pure performance requirements. For example, instead of providing many hundreds of pages of specifications for the design and installation of lighting equipment, we would instead establish a requirement expressed in lumens measured at a height of 36 inches above the floor. This did two things. First, it allowed competitors to use their ingenuity and creativity in developing innovative solutions to meet our requirements. Second, it provided a clear and unequivocal measure of required performance so that determinations of success or failure to meet our requirements could be objectively measured.

The effect of this change was revolutionary. Compared to the 3,500 page spec package required for Wedge One, the spec package for Wedges Two through Five (an area of more than four million square feet) totaled a mere 16 pages. Interestingly, the result was clearer communication with regard to our requirements and less ambiguity with respect to our expectations of contractor performance.

At the same time, moving to pure performance specifications presented us with new challenges. How could we ensure that we had not opened the gates to creative larceny, with contractors using their creativity and ingenuity to “game the system” by providing us with inferior products and services? And how could we accomplish meaningful source selection decisions when it seemed that everyone would be competing with different vision of the work to be accomplished? Would we trigger a massive rush to provide only the meanest products and quality? How could we avoid opening ourselves to a flood of mediocrity?

We addressed this challenge by stripping the often-complex source selection process down to its two basic components: price and technical content. Traditional design-bid-build defines technical content in great detail, freezing its characteristics and holding them static. Competition is achieved by allowing price to vary, with award being made to the low bidder. For our design-build competition, we inverted that relationship. We froze price and held it static. Competition would be achieved by allowing technical content to vary, i.e., we would build to budget, and competitors would win in the competition by demonstrating their ability to most effectively meet our requirements. Successful competitors would be the best, not the cheapest.

The above colored overlay identifies each phase of the design-build renovation of the Pentagon Renovation Program. Wedge 1 (one million square feet of space) was the first area to undergo renovation, followed by Wedges 2-5 (four million square feet total).

The above colored overlay identifies each phase of the design-build renovation of the Pentagon Renovation Program. Wedge 1 (one million square feet of space) was the first area to undergo renovation, followed by Wedges 2-5 (four million square feet total).Another problem inherent in design-bid-build is that competitive pressures often force competitors to bid unrealistically low prices. In discussions, I learned that it’s common for bidders to knowingly submit bids well below cost. Once awarded the contract, firms would then seek to find irregularities, conflicts or other errors in the designs and specifications, making the case for issuance of a change order through which the bidder could become financially whole. Unfortunately, once engaged, change order mentality becomes self-reinforcing and develops a poisonous inertia. Paradoxically, the focus on cost in a design-bid-build often causes the owner’s most powerful tool (control of a contractor’s profit) to diminish or disappear entirely. In the Pentagon Renovation Program, we wanted to maintain a healthy profit opportunity so that our role as the arbiters of profit would be enhanced. We wrestled with how best to achieve that goal.

Combining two streams of thought, we devised a build-to-budget approach that establishes a fixed price and at the same time fences profit opportunity. We were determined to ensure profit opportunities within the Pentagon Renovation Program operated at rates highly attractive to the industry in order to promote aggressive competition among highly qualified companies for our work.

Ultimately, we implemented an award fee approach that periodically placed an amount of award fee profit on the table. Based on an evaluation of the contractor’s performance, some percentage of the available profit would be awarded to the contractor. In addition, we provided a shared savings provision which would split cost savings 50/50 between the contractor and the government, as long as the contractor first performed at a high level in the award fee evaluations. No savings were shared unless the contractor first achieved at the required high level of award fee performance. The result was that the contractor was rewarded for quality performance and rewarded for cost efficiency.

Combining these innovative approaches with many others, we developed an approach that we believed would attract superlative contractors and motivate them to provide world-class performance. But, the solutions we devised cut across accepted industry practice. We needed an opportunity to show it would actually work—something big, challenging and highly visible so it would quiet the voices already railing against us. That opportunity came as the result of the unfortunate events that soon unfolded in the Oklahoma City bombing. Suddenly, Congress voted money to build the Pentagon Remote Delivery Facility, a badly needed project the Pentagon had been attempting to get funded for years. The catch was, Congress wanted the building completed immediately and there were neither drawings nor other documents available.

I was called one afternoon to the office of David O. (Doc) Cooke, head of Washington Headquarters Services. Known in the business as the “Mayor of the Pentagon,” Doc was a force of nature, known for being on a first-name basis with senators and representatives. He had a jolly appearance, but appearances were deceiving. He’d held his job for decades because he was smart, hard-charging and ruthless, and he wasted no time getting to the point. “I’ve noticed that you Pentagon Renovation guys actually get things done,” he said, “and that’s a rare commodity in these parts.”

He continued, “I want you to build the new Remote Delivery Facility and I want it done in one year,” he said. The time frame was more than ambitious.

“I’ll take the job, with one proviso: that I get to do it my way,” I replied.

Doc looked across his great desk, an aircraft carrier-sized mahogany monolith. “Do it any way you want. Just get it done in a year.” We shook on it.

Eleven months later I reported to Doc that we had completed the project a month ahead of schedule and that daily deliveries were being made as we spoke. I also asked him how he wanted me to spend the four million dollars we had left over.

Doc laughed. “You just said two things that I haven’t heard at the Pentagon in many, many years: A project is done early and money is left over. Good job.”

You couldn’t get much higher praise. We had rolled the diced and won.

Aspirational Contract Principles

“This contract reflects a significant departure from traditional government-dictated design practices and associated program controls, and substitutes to the greatest degree possible the contractor’s standard commercial practices.”

“In exchange, it’s the contractor’s responsibility to adapt these commercial practices, if necessary, to provide the government with an acceptable level of insight and participation, during design and construction, as befits an informed consumer.”

“The contractor and the government will form a unified co-located team to jointly manage the project activities described in this document.”

“The team is jointly responsible for solving all problems that arise.”

“The expected period of performance for the contract is in excess of 10 years. Although the contract has been written in contemplation that changes will undoubtedly occur, there is no reasonable expectation between the parties that the contract in fact addresses all possible changes that will occur. In fact the parties understand that it would be impossible to write such a contract. What is needed instead, and what this contract does address, is the nature of the relationship between the parties.”