Some have a beautiful, linear fluidity, as if prepared by a genealogist. Others look more like a complicated offensive play, drafted on a chalkboard by some diabolical coach. Organizational charts are one of the most mismanaged items in construction firms. How can a piece of paper create so much controversy?

More importantly, why is it essential that an organization maintain such a simple illustration? Organizational charts are a tool to support the firm's strategy and overall structure. However, there are many instances in which this innocuous tool has morphed into a document that undermines a firm's master strategy or a flimsy piece of paper hardly worth the page on which it's printed.

The Dreadful Dotted Line

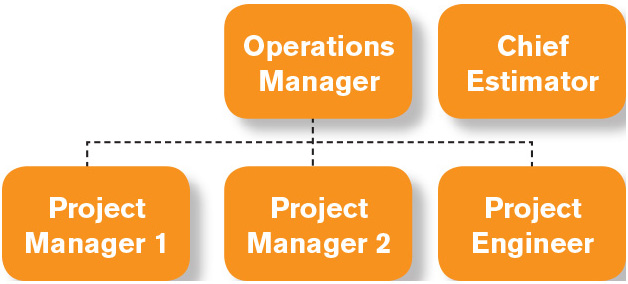

One of the biggest mistakes in the development of organizational charts is the use of the dotted line. It is understandable that an individual might have some influence from various departments. For instance, in Figure 1, an estimator might have responsibilities that straddle both business operations and business development.

Figure 1. The dotted line sometimes leads to departmental confusion.

At first glance, it appears that this project engineer simply operates within two different departments. This is a fairly common practice, especially for new talent learning the inner workings of a firm. However, this has become less a practice to help new associates and more a lazy management tool. The result is a group of individuals with multiple bosses. To test this in your own organization, ask any individual who they report to (short of the president or CEO) and gauge the answer.

Common scenarios include:

- Safety directors/managers who report to the operations manager and the president

- Field supervision who report to managers and executives

- Operational support (equipment, BIM, purchasing, warehouse) with multiple bosses within the firm

- Firms with combined project managers and estimators rather than separate project managers and estimators

How did this structure evolve? The answer may be one of the following:

Firm growth—The firm continues to grow, but its organizational structure doesn't evolve with growth.

Personalities—How often do leaders hear, "I can't work for him or her," which leads to some informal reporting structure? Maybe there is the risk of offending someone if a subordinate is removed or added.

Project delivery—The overarching approach of the firm changes, but the existing structure simply bolts on to the new operational model.

Apathy—If it isn't broken, why fix something as mundane as the organizational chart?

The next question you should ask is, "Why?" Does the dotted line serve a purpose, such as employee development and growth, or is it simply a holdover from a bygone strategy?

Strategy

Often, a firm has an organizational structure that mimics an anchor—one that confines and restricts a firm's growth, dragging it down to the seabed. Strategists have long held the mantra, "Strategy first, then structure." Consider how often a firm looks at its strategy and business plan, only to lament, "We would love to look at that market or niche, but we just don't have the capability." While this may be true, in many cases, firms have become slaves to organizational structures and all of the conventions that go along with them. Often, it is the fear of disrupting the status quo. Put another way, the solid lines of the organizational chart have become too rigid, restricting any firm flexibility and growth.

A firm should routinely examine its strategic focus. If the firm finds itself saying, "We can't do that because we aren't structured that way," it may be time to realign. This does not mean you have to change just for change's sake, but you must maintain a certain nimbleness to achieve a firm's strategic goals.

Career Progression

For many years, organizations marched toward creating flatness. Horizontal organizational charts became popular in an effort to appease a generation that viewed a company's hierarchy as cumbersome and restrictive to career progression. "Think about it—you are one step away from the president." These words inspired an entire generation.

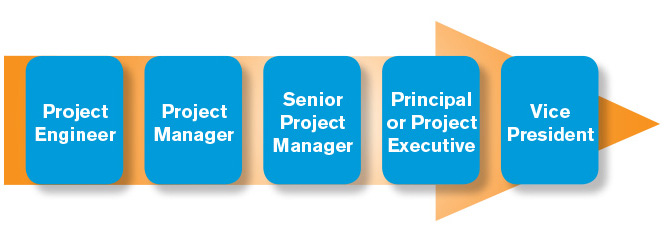

Figure 2. The most important element of career progression is the responsibility that each position demands.

Hire on as a project manager and migrate to the position of president. It may be important to reconsider this model. Younger generations may not view this with the same excitement that their predecessors did. In many cases, there is already a"financial hierarchy" in place—senior managers make more money than junior managers. One solution would be to create roles and responsibilities that are commensurate with this salary structure. Many firms have this structure in title only. For example, countless firms have "project executives."

The one caveat to that is this—do they serve as true executives, or is this more of a title in recognition of tenure? One additional organizational chart mistake is the reliance simply on the hierarchical roles and less concern for the actual responsibilities. As represented in Figure 2, the most important element of this career progression is the responsibility that each of the aforementioned positions demand. A vice president should be a strategic leader within the firm, not just a simple title to denote experience.

The Position, Not the Person

Within the construction industry, there are high numbers of family-owned enterprises. This will always be an incredibly positive attribute and driving force within the industry. However, there are also unique burdens that family businesses must deal with proactively, and the organizational chart often serves as one such challenge. For example, there are many instances in which positions are created simply because there are few other options. It is easy to sit on the outside of a business and question the intent of a decision, particularly one that involves family. Important considerations that any leader must examine can include:

The message today—What does this say to the rest of the organization? What does this say to the high performers within the firm that may be part of the firm\'92s long-term continuity?

The future—Does a decision today hamstring the firm in the future? Will the organizational structure create a legacy problem for the next generation?

This is not exclusive to family businesses. As stated previously, there may be a passivity when it comes to confronting the brutal facts about a firm's current talent. Are leaders willing to deal with associates that may not have the capabilities, when the alternative is creating a structural nightmare? Organizational charts are not meant to lead the firm and are never a substitute for true management, guidance and strategy. They simply memorialize the roles and responsibilities and help a true leader run the business well. Charts should be examined routinely to ensure they are serving the right purpose in the short and long term. Leaders must create these charts as dynamic tools that help them drive their businesses forward. A true organizational chart is only the first page in the strategic playbook.